Table of Content

- Introduction

- Hmm, So What Exactly is Parsing?

- How does Parsing Work?

- Environment Setup

- Project Setup

- Writing The Tokenizer (Lexer)

- Context-Free Grammar (CFGs)

- Writing The Parser

Introduction

This post is long and rather technical, you might want to grab a coffee for this

Parsers are crucial in the technology we use daily as software engineers, from code linting and syntax analysis to interpreters and compilers. There's no doubt understanding (to a certain extent) the intricacies of how they work can give valuable insights and help you level up as a programmer.

We'll build a flavor of parsers known as "Recursive Descent Parsers", which use a set of mutually recursive functions to elegantly parse any valid JSON string.

In this blog post we'll mostly focus on the tokenizer, and in part 2 we'll write the actual parser. I'll be implementing our parser in Rust, but even if you're not a fan of the language, you can always reproduce this in any language you like. (bonus points if you choose C).

Here's the official JSON specification as a guide.

Hm, So What Exactly is Parsing?

Doing a quick Google search, we have:

Parsing, syntax analysis, or syntactic analysis is the process of analyzing a string of symbols, either in natural language, computer languages, or data structures, conforming to the rules of a formal grammar.

Note the keyword "formal grammar". It's the instructions telling our parser how to deal with each token it encounters. In Recursive Descent (RD) Parsing, each "non-terminal" is defined as its own recursive function that yields a result; and starting from the root non-terminal, others are called recursively. Don't worry if you don't know what a "non-terminal" is yet, we'll go over that later.

Alright, alright, that sounds cool and all, but why should I bother writing my own parser you ask? There are tons out there already! Good question! Well, if you're like me, who's very curious about what makes these tools tick, then I'm sure you're going to enjoy learning and implementing your own from scratch!

Plus, if you're going to write your own programming language (or compiler) someday, you can't escape parsing theory ;)

How does Parsing Work?

Parsing is broken down into two major stages:

- Tokenization (lexical analysis), and

- Parsing (actual parsing)

Tokenization:

This is the process of classifying parts of the string as tokens (or lexemes) so that the parser can work with them. For instance, let's look at this JSON file content:

{

"name": "Rust",

"version": 1

}Several tokens are present here, for example, those braces "{" and "}", so our program will have tokens corresponding to the left and right braces. There are also a couple of strings in there, so we'd have a "string" token too. Notice the colon (:) and commas (,), these would have their corresponding tokens. You get the idea; things like whitespace are generally ignored.

Parsing:

This is where the actual magic happens, our parser takes a list of the tokens we extract from the tokenization stage and converts them into something useful. JSON looks a lot like a standard computer science hash map, so we'll convert our JSON string into a Rust hash map.

Environment Setup

We're writing the parser in Rust so I assume you have the binaries installed on your system. If not, you can head over to their docs and follow the instructions for your OS. I'm on a Linux build so installation is fairly simple:

$ curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf <https://sh.rustup.rs> | sh

$ rustup --versionProject Setup

Let's set up a new Rust project using cargo and open it up.

$ cargo new json-parser

$ cd json-parserWriting The Tokenizer (Lexer)

Ok, we're in, firstly I'll change the classic "Hello World" to "JSON Parser"

fn main() {

println!("JSON Parser");

}Compiling this using cargo run you should get the output "JSON Parser", alright. We're good to go. Let's start by getting user input. You can delete the println macro.

use std::io::{self, Write};

fn main() {

let mut json_path: String = String::new();

print!("> JSON File Path: ");

io::stdout().flush().unwrap();

io::stdin()

.read_line(&mut json_path)

.expect("Could not read file path.");

let json_path: String = json_path.trim().to_string();

println!("\n{json_path}");

}Let's break this down. First, we're creating a mutable string reference, json_path to hold our json file path. Then we flush the input buffer before reading input. We're going to use trim() to remove any leading or trailing whitespace that might be present and finally, we print the result. Running this, you'd get prompted for a path and it gets printed!

Ok but staring at a string isn't interesting, we want to read the contents of the file it points to (if it exists). Let's create a reader module. It'll be in charge of reading and processing any paths we pass to it.

mod reader;

use std::io::{self, Write};

fn main() {

// rest of main

}$ clear

$ touch src/reader.rsuse std::{fs, io::Error};

// Read a json file from path

pub fn read_json(path: String) -> String {

if !path.contains(".json") {

panic!("File path: '{}' does not contain a json file.", path);

}

let read_result: Result<String, Error> = fs::read_to_string(path);

let content: String = match read_result {

Ok(file ) => file,

Err(_) => panic!("Invalid file path or file does not exist.")

};

return content;

}That's all we need for our reader module. We receive a file path and first of all check if there's a .json extension to it. After that, we simply read the file using the fs standard library function, then return the contents as a string result.

I've updated main.rs to use the reader now.

mod reader;

use std::io::{self, Write};

fn main() {

// Earlier code

let json_path: String = json_path.trim().to_string();

let mut content: String = reader::read_json(json_path);

println!("\n{content}");

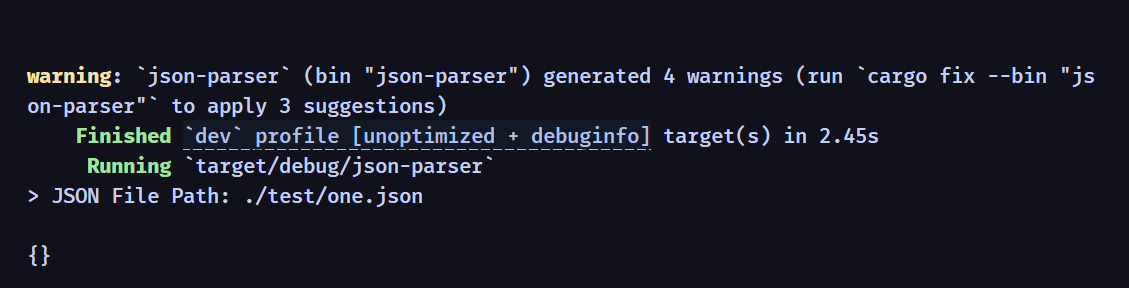

}And just like that, we can read files now. Pretty cool if you ask me. I'll create a test folder and create a file one.json to see what our program prints.

$ clear

$ cargo runThis is my ouput! Everything is working perfectly so far, super nice. Let's get started with the tokenizer.

The Token Struct

In this section, we'll implement our tokenizer to handle most of the tokens recognized by the JSON standard.

Before we write the code, we need to understand the structure of a token. Our token is composed of two parts, a “kind” and an optional “value”. The kind of a token can be any of: string, number, boolean, left brace, right brace, etc as per the official JSON specs. Here's a list of all the tokens our parser will handle.

- Left brace

- Right brace

- Colon,

- Comma,

- String,

- Number,

- Object,

- Boolean,

- Null

I've gone ahead and created a new file, token.rs. We'll represent JSON tokens as structs with their kinds as enums.

// Token kind

#[derive(Debug)]

pub enum TokenKind {

LBRACE,

RBRACE,

COLON,

COMMA,

STRING,

NUMBER,

BOOLEAN,

NULL

}

// Formatting for display: token kind

impl TokenKind {

pub fn debug(&self) {

println!("{:?}", self);

}

}Each enum entry corresponds to a token we'll handle in the parser. For the actual token struct:

// Earlier token kind code

// Token struct, each token has a 'kind' and value

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct Token {

pub kind: TokenKind,

pub value: Option<String>

}

// Formatting for display: token

impl Token {

pub fn debug(&self) {

println!("kind: {:?}, value: {:?}", self.kind, self.value);

}

}So each token will have the kind attribute. Some tokens can have a value, like strings and numbers. Everything else won't. I've decided to keep the tokenizer separate from the token file since I feel it's cleaner that way.

I've created a new file for the tokenizer and started with handling braces.

$ touch src/tokenizer.rs

$ code src/tokenizer.rsuse crate::token::{Token, TokenKind};

// Tokenizer struct

pub struct Tokenizer {

pub pos: usize,

pub source: String,

}These are the states we'll track. the pos attribute holds our current position in the string. The source attribute is the actual string content.

use crate::token::{Token, TokenKind};

// Tokenizer struct

pub struct Tokenizer {

pub pos: usize,

pub source: String,

}

// Methods

impl Tokenizer {

// Tokenize a valid JSON string

pub fn scan(&mut self) -> Vec<Token> {

println!("{}", self.source);

let mut tokens: Vec<Token> = Vec::new();

let char_vect: Vec<char> = self.source.chars().collect()

// Panic on trailing chars

let trailing: char = char_vect[char_vect.len() - 2];

if !trailing.is_alphanumeric() && trailing != '{' && trailing != '}' {

panic!("Unexpected trailing character: '{}'", char_vect[char_vect.len() - 2]);

}

}

}The tokenizer starts with the scan() method. First of all, we need a way to work with the individual characters in our string; that's where the char_vect comes in. It's a vector of UTF-8 characters. Our tokenizer will work through each character; ignoring whitespaces; and add them to the tokens vector. You can think of a Rust vector as a regular array found in most programming languages.

The code in the last few lines ensures that our string ends with a proper alphanumeric character or brace.

Handling braces is simply a matter of checking whether the character matches "{" or "}". While we're at it, let's also handle commas (,) and colons (:).

// Earlier code inside scan()

// Iterate till the end

while self.pos < self.source.len() {

let lexeme: char = char_vect[self.pos];

match lexeme {

'{' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::LBRACE,

value: None,

}),

'}' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::RBRACE,

value: None,

}),

':' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::COLON,

value: None,

}),

',' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::COMMA,

value: None,

}),

}

}

return tokens;This code iterates through our source string till we run out of characters to look at. The lexeme variable keeps track of the current one, then inside our match expression, we push the right type of token to our token vector.

Nice. This handles pushing the proper tokens efficiently. Doing good.

So far, we've only looked at tokens that don't have a value. How do we handle things like strings? Are we going to create match expressions for every possible combination of strings there are in the universe?!

And no, of course, we won't do that, that's horrible. What we will do tho, is track when a string starts and ends. In JSON, strings are enclosed in double quotes ("), so a smarter approach is to just switch to "string scanning mode" whenever we see a quote and exit when we encounter its closing quote.

So let's start by tracking when we're in a string:

// Earlier code inside match

'"' => {

self.advance(); // consume '"'

if let Some(res) = self.scan_str() {

tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::STRING,

value: Some(res),

})

}

}Running this, you'd get screamed at by Rust because we haven't defined the advance() or scan_str() function yet. Let's start with advance, outside our scan function.

// Advance one character forward

fn advance(&mut self) -> Option<char> {

if self.pos < self.source.len() {

self.pos += 1;

return self.source.chars().nth(self.pos - 1);

}

return None;

}The objective is simple. Move the pointer forward and return the character right before it. This function will only return something as long as we've not exceeded the source string length.

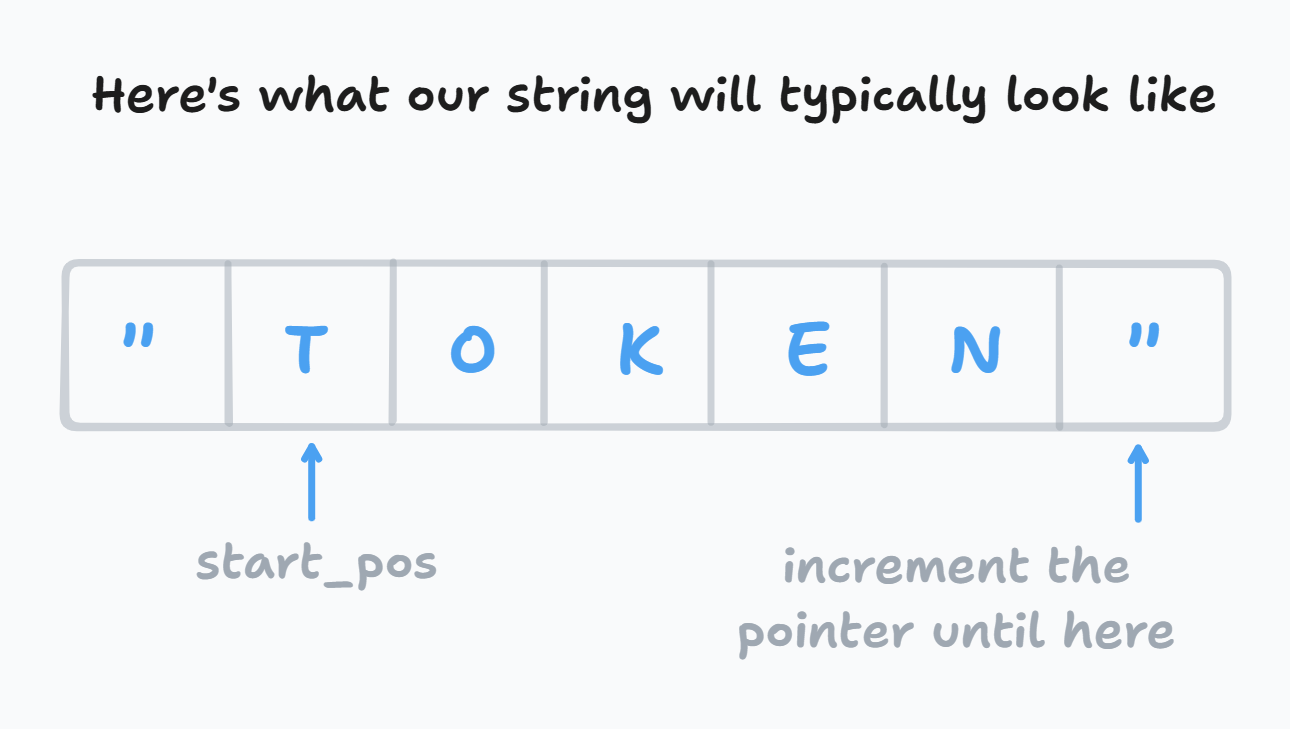

For scanning strings here's the approach:

// Tokenize string values

fn scan_str(&mut self) -> Option<String> {

let start_pos: usize = self.pos;

// Iterate till closing quote or EOF

while (self.pos + 1) < self.source.len() {

if self.peek().unwrap() == '\0' {

panic!("Unexpected EOF at pos: {}", self.pos);

}

if self.peek().unwrap() == '"' {

self.advance();

return Some(self.source[start_pos..self.pos].to_string());

}

self.advance();

}

return None;

}So, what have we here? The string scanning works by keeping track of the start position (right after the quotes) and the end right before the ending quote.

I'm first checking for an EOF character which is how we tell programs where the END OF a FILE is, and throw an error if we encounter one before the closing quote.

Most of the action is just "peeking" at which character comes next and while it's not a quote, we update our current position. If it is, we simply consume that quote, and then return a slice from our start to end positions.

But there's an issue, Rust has no idea where to find the peek() function. It's just like our advance function but it doesn't update the pointer. So let's implement that.

// Inside the impl block

// Peek one character forward

fn peek(&self) -> Option<char> {

if self.pos + 1 < self.source.len() {

return self.source.chars().nth(self.pos + 1);

}

return None;

}Looks good. In the meantime, let's add a catch-all to panic whenever we encounter unknown tokens:

// Earlier code inside scan()

// Iterate till the end

while self.pos < self.source.len() {

let lexeme: char = char_vect[self.pos];

match lexeme {

'{' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::LBRACE,

value: None,

}),

'}' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::RBRACE,

value: None,

}),

':' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::COLON,

value: None,

}),

',' => tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::COMMA,

value: None,

}),

'"' => {

self.advance(); // consume '"'

if let Some(res) = self.scan_str() {

tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::STRING,

value: Some(res),

})

}

},

_ => {

panic!("Unexpected character '{}' encountered at pos: {}", lexeme, self.pos);

}

}

}

return tokens;Finally, I'll update the main.rs file to use these modules.

mod reader;

mod token;

mod tokenizer;

use std::io::{self, Write};

use token::Token;

use tokenizer::Tokenizer;

fn main() {

// previous code

// Read file and return contents

let mut content: String = reader::read_json(json_path);

let mut lexer: Tokenizer = tokenizer::Tokenizer {

pos: 0,

source: content.trim().to_string(),

};

let tokens: Vec<Token> = lexer.scan();

for i in 0..tokens.len() {

println!("{:?}", tokens[i]);

}

}You can try it on this JSON string, everything should still be working.

{

"name": "json-parser"

}Sweet, we can theoretically handle any string now, let's crack numbers next!

We can handle numbers just like how we did for strings. We can just track when we encounter a numeric character and increment our pointer until we see another kind of character. Our JSON parser should be able to identify negative numbers, so let's keep that in mind.

// Earlier code inside match

'0'..='9' | '-' => {

let mut num: String = String::new();

if lexeme == '-' {

num.push('-');

self.advance(); // consume "-"

}

if let Some(res) = self.scan_num() {

num += &res;

tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::NUMBER,

value: Some(num),

})

}

self.pos -= 1; // reset cursor

}What this code does is checking whether the current lexeme is a number, i.e. between 0 to 9, or starts with a minus sign. If it's a minus sign, we consume it and move forward. Since we're in the numbers domain now, we'll delegate scanning the number to another function: scan_num(), then push the result to our token vector.

We have to reset our pointer at this point since after scanning we'd be an extra character ahead.

My implementation of scan num is similar to scan str:

// Inside impl block

// Tokenize number values

fn scan_num(&mut self) -> Option<String> {

let start_pos: usize = self.pos;

let mut has_decimal: bool = false;

while (self.pos + 1) < self.source.len() {

let next: char = self.peek().unwrap();

if !next.is_numeric() && next == '.' && !has_decimal {

has_decimal = true;

self.advance();

} else if next.is_numeric() {

self.advance();

} else {

self.advance();

return Some(self.source[start_pos..self.pos].to_string());

}

}

return None;

}Notice how I'm tracking whether the number has decimal points. All that's going on here is checking the next character is still numeric, then updating our pointer if it is. If it isn't, we consume that last numeric then return a slice up until that point.

This is 80% of the tokenizer done. Finally, we have to handle things like booleans and null, that aren't exactly strings.

// Impl block, just before scan()

// Tokenize identifiers (true/false/null)

fn scan_identifier(&mut self) -> Option<String> {

let start_pos: usize = self.pos;

// The longest identifier is "false" of length 5

// So let's track the next four characters

if (self.pos + 4) <= self.source.len() {

let next_four: String = self.source[start_pos..(self.pos + 4)].to_string();

if next_four == "null" || next_four == "true" {

self.pos += 4;

return Some(next_four);

} else if (self.pos + 5) <= self.source.len() {

// If the next five is "false" instead

let next_five: String = self.source[start_pos..(self.pos + 5)].to_string();

if next_five == "false" {

self.pos += 5;

return Some(next_five);

}

}

}

// An invalid token, panic()

panic!("Unexpected identifier: '{}' at pos: {}", self.source[start_pos..self.pos].to_string(), self.pos);

}The logic for scanning identifiers is simple: We know an identifier won't exceed 5 characters, so I'll move the pointer 4 characters ahead to see if it matches "true" or "null" and then return the appropriate string.

Otherwise, check the next five characters if they match "false" and return that instead. If we have whatever garbage value that isn't true, false, or null, panic on execution.

Panics in Rust are similar to throwing errors in other programming languages.

We're close to finishing our tokenizer, all that's left is to use the scan_identifier() function.

_ => {

if lexeme.is_alphabetic() {

if let Some(res) = self.scan_identifier() {

if res == "true" || res == "false" {

tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::BOOLEAN,

value: Some(res),

})

} else {

tokens.push(Token {

kind: TokenKind::NULL,

value: None,

})

}

self.pos -= 1;

}

} else {

panic!("Unexpected character '{}' encountered at pos: {}", lexeme, self.pos);

}

}We switch to identifier scanning mode when we encounter an alphabetic character that isn't one of our earlier matched expressions, and push their tokens to our vector.

Yay! Our tokenizer is done and ready now. You can throw in any well-formatted JSON string and the tokenizer will spit out a vector of tokens and values. In the next section, we'll tackle the parser module.

The tokenizer is the time-consuming part of the system, I promise the parser module will be easier lol.

Context-Free Grammar (CFGs)

Now you're almost ready to write the parser, but you need to know what a context-free grammar is first. Remember how we said we need a formal grammar in order to parse strings? That's where CFGs come in. CFGs give us a formal way to mathematically model smaller units of a grammar into composable forms. There's a lot of factors that come into choosing a grammar; things like avoiding left recursion or infinite recursions.

This is what ours will look like:

object ::= '{' members '}'

members ::= pair(',' pair)*

pair ::= string ':' value

value ::= string | number | object | boolean | nullEach object starts with a left brace literal, a member and then a right brace literal.

Members contain what we call pairs. The pair(, pair)* syntax means a pair can contain other pairs or comma separated pairs. That asterisk (*) means it can also repeat indefinitely.

Pairs are composed of a string and a value separated by colons.

Values can be any of: string, number, object, boolean, or, null.

Defining our grammar in this way ensures we can create recursive functions that call themselves in just the right way to build a complex, yet effective hierarchy of tokens.

CFGs can quickly become rather complex, if you're interested in learning, more I strongly recommend you check out the wiki.

Writing The parser

We've achieved a lot in this blog post! And congrats if you made it this far, here's a pat on the back for you (lol). We'll implement the parser extensively in part 02, so watch out for that! In the mean time, you can test our tokenizer with lots of json strings to see if it works fine, or you could extend it to handle exponential numbers, if you're feeling up for it!

Questions, comments or suggestions? Ping me a mail at ssh.xero@gmail.com or @_xerodev on Discord, and I'll get back to ya!